NO oder war es NOT? / NO or was it NOT?

Ausstellung / exhibition Kuckei + Kuckei, Berlin 10. Dezember bis 4. Februar 2006

nicht gemalt / not painted, 2003 Acryl auf Leinwand, acrylic on canvas, 55 x 40 cm

zensiert von Matten Vogel / Censored by Matten Vogel, Motiv Nr. 1, 2002 Iris Print, 100 x 60 cm

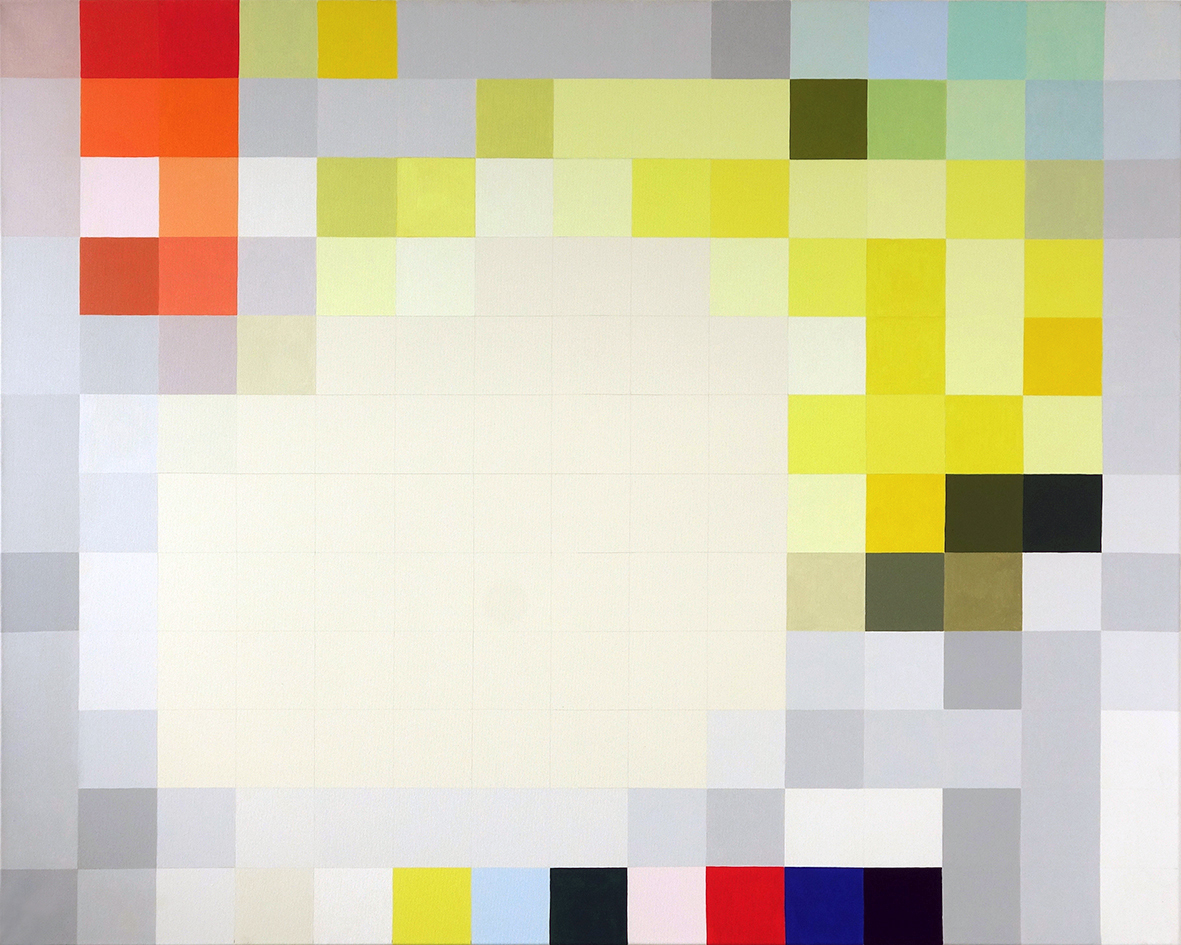

not 37, 2005 Acryl auf Leinwand, acrylic on canvas, 120 x 150 cm

not 47, 2005 Acryl auf Leinwand, acrylic on canvas, 120 x 150 cm

NO oder war es NOT?

Wir werden Zeuge eines klassischen Abstraktionsvorganges: Ein partikulares Motiv wird in ein allgemeines Raster überführt, das Abbild einer visuellen Erscheinung wird überwunden, um zu einer Idee, einer Essenz, Substanz, Struktur oder eben zum Quadrat (und manchmal auch zum Pixel) vorzudringen. Das ist Teil des Vorgangs dessen Ergebnis wir in Matten Vogels Serie Not sehen. In all seinen unterschiedlichen Spielarten bestimmte dieser Vorgang wie kein anderer das Kunstgeschehen des letzten Jahrhunderts, man könnte fast sagen das er das Grundmotiv der Moderne ist: Das Partikulare in ein Allgemeines zu überführen, oder im Partikularen die Kompositionsregeln des Allgemeinen herauszuarbeiten. Das gilt keineswegs nur für die Kunst, sondern gleichermaßen für die Entwicklungen in der Politik und der Verwaltung der Gesellschaft, mit den bekannten „Schattenseiten,“ die mit der Absolutheit und „Reinheit“ von allgemeinen Kategorien verbunden sind. Dem Vorgang der Abstraktion sind auf eine Weise auch chemische Prozesse etwa der Reduktion, der Essentialisierung, der Isolierung verwandt. In der Mathematik und Politik könnte man Vergleiche zur Mengenleere ziehen, die Elemente bestimmter Eigenschaften bestimmt, oder in der Sprachwissenschaft an die „leeren Signifikanten“ denken, soziale Zeichen wie etwa die Idee der Nation (das berühmte Beispiel hier ist das Denkmal des Unbekannten Soldaten), die einen extrem hohen Abstraktionsgrad aufweisen, der erst durch die Imagination des Einzelnen mit konkretem Inhalt gefüllt wird und so einen Realitätsgehalt bekommt, sich verkörpert. Später wurde die Idee der Essenz selbst auf vielfältige Weise abgelehnt und als diskursive Konstruktion demaskiert– womit die Suche nach dem Abstrakten an sich durch die Geste (und damit die Möglichkeit, den Prozess) der Abstraktion als den zentralen Vorgang der Bedeutungsproduktion ersetzt wurde. Von den „leeren Signifikanten“ ist es nicht mehr weit zum anderen Element in Matten Vogels Not Bildern: Der Leere, aber auch dem Testbild. Die Bilder, die wir jetzt sehen, haben sich aus zwei vorhergehenden Serien entwickelt: Der Reihe „zensiert von...“ und der Reihe „nicht gemalt“. In „zensiert von...“ werden schwarze Zensurbalken über zentrale und beiläufige Elemente innerhalb gefundener fotografischer Motive gelegt: Gesichter meistens, jedoch auch ein Schiff in der Bildmitte. Das hat vielleicht weniger mit Zensur als solcher zu tun gehabt, als mit der Geste, etwas zum Verschwinden zu bringen, und genauer noch, das Zentrum, den Focus, zum Verschwinden zu bringen: Das Gesicht, die Augen, die sowieso Zentrum sind, oder das Motiv in der Bildmitte. „Zensiert von...“ ist damit eine Annäherung an die Gestik der Macht schlechthin: Macht als Potenz, ein Partikulares oder Singuläres in einem Allgemeinen aufzulösen oder es auszulöschen. Die Serie „nicht gemalt“ ist wie eine Testreihe zu den jetzt zu sehenden Bildern: In klassischen gemalten Genremotiven werden große Flächen „ausgespart“. Das ist schon ganz anders als die Geste des Zensurbalkens, arbeitet sich aber an der Malerei ab, die einen starken Sog ausübt. In Not ist das Motiv der leeren Mitte aus dieser Umklammerung des gemalten Motivs gelöst, eine Umklammerung, die eben immer noch an Aussparung, Ausmalen etc. denken ließ. Die Grenze zwischen gemalt und nicht gemalt ist jetzt fließend und doch absolut: Das Motiv (die Bilder bauen auf der Serie „nicht gemalt“ auf) ist in gleichmäßige monochrome Farbflächen zerlegt, die einem über die ganze Bildfläche gelegten Raster folgen. Die leer gelassenen Farbflächen in der Bildmitte werden damit zu einer eigentlichen Leere, zur Leere des Zentrums. Es kann sowohl eine Geste der Negation sein (der Titel weist darauf hin) als auch eine raum-schaffende Geste, oder eine Meditation, was an die Organisationsprinzipien japanischer Gärten und Städte denken ließe, deren Machtzentrum ebenfalls eine Leere beschreibt. Es kann sich aber auch um einen im erweiterten Sinne „optischen“ Effekt- oder Defekt handeln, eine Unmöglichkeit zu fokussieren, zu identifizieren und das Eigentliche, Essentielle zu erkennen, immer an den Rand der Sehfläche gedrängt zu werden, wo Identifikation möglich, aber immer schon partikularisiert ist – das Allgemeine ist eine notwendige Fiktion, es lässt sich nicht identifizieren. Die aus dem Fernsehen entliehenen Testbild-Streifen am unteren Bildrand weisen darauf hin, und führen gleichzeitig das Element der modularen und maschinellen Norm in die Bilder ein. Die leere Mitte steht hier in einem sich ständig neu definierten, reziproken und doch immer hierarchischen Verhältnis zum identifizierbaren Rand, während das Grundraster für deren gemeinsame Verfassung steht. Es ist die allgemeine Leere, die dem Partikularen ihren Platz zuweist, gleichzeitig aber ist die Leere auch eine Abwesenheit und sogar ein Mangel an Partikularem. Man kennt das Konzept der „Leeren Mitte“ auch aus politischen und sozialen Theorien: Die Leere Mitte der Macht erlaubt und zwingt das Partikulare, sich identifizierbar zu machen, eine Identität anzunehmen, sich zu verordnen, spezifisch im Verhältnis zum Allgemeinen zu werden. In dem Moment, wo jedoch die Autorität selbst identifizierbar wird, wird sie auch angreifbar und häufig allzu schnell an den Rand gedrängt. In diesem Sinne ist die leere Mitte in den Bildern Not ein pulsierendes und doch hermetisches Zentrum, dass das virulente Problem der Notwendigkeit der Leere als Verlust und Gewinn exemplifiziert.

Anselm Franke

NO or what it NOT?

We become the witnesses of a classic process of abstraction: a particular motif is transferred to a general grid, and the reproduction of a visual appearance is transcended to advance to an idea, an essence, substance, structure, or simply to a square (and sometimes a pixel. This is part of the process whose result we see in Matten Vogel’s series Not. In all its variants, this process determined like no other the course of art in the last century; one could almost say it is the basic motif of Modernism: to translate the particular into a generality or to work out in the particular the laws of composition of the general. This is true not only of art, but equally for developments in the politics and administration of society, with the well-known “shadow sides” that are connected with the absoluteness and “purity” of general categories. In a certain way, chemical processes like reduction, essentialization, and isolation are akin to the process of abstraction. In mathematics and politics, one could make comparisons to set theory, which categorizes elements with specific qualities; in linguistics, one could think of the “empty signifier”, social signs like the idea of the nation (the famous example here is the monument of the Unknown Soldier), which display an extremely high degree of abstraction that requires the individual’s imagination to fill it with concrete content, thereby taking on substance and embodiment. Later, the idea of essence was itself in many ways rejected and demasked as a construction of discourse – with which the search for the abstract in itself was replaced by the gesture (and thereby the possibility, the process) of abstraction as the central process of producing meaning. It is not far from the “empty signifier” to the other element in Matten Vogel’s Not pictures: the void, but also the test image. The pictures we now see have developed out of two previous series: “ zensiert von...” (censored by...) and “nicht gemalt” (not painted). In “zensiert von...”, black censorship bars are laid across central or incidental elements of found photographic motifs: faces, usually, but also a ship in the middle of the picture. This may have less to do with censorship itself than with the gesture of making something disappear – more precisely, with making the center or focus disappear: the face, the eyes, which are the center anyway, or the motif in the middle of the picture. “Zensiert von...“ is thereby an approach to the gesture of power as such: power as the potency to dissolve or extinguish something particular or singular in a generality. The series “nicht gemalt” is like a series of tests for the pictures we now see: in classically painted genre motifs, large surfaces are “cropped away”. This is quite different from the gesture of the censor’s black bar, but it expends itself on the painting, which exerts a powerful pull. In Not, the motif of the empty middle is released from this embrace of the painted motif, an embrace that still makes us think of cropping, painting over, etc. The boundary between painted and not painted is now fluid and yet absolute: the motif (the pictures build upon the “nicht gemalt” series) is divided into even, monochromatic fields of color that follow a grid laid over the entire picture surface. The fields of color left empty in the center of the picture thus become an actual emptiness, the emptiness of the center. This can be a gesture of negation (the title points to this) or one of creating space, or a meditation that recalls the organizational principles of Japanese gardens and cities, whose center of power also describes a void. But it can also be, in a broad sense, an “optical” effect or defect, an impossibility to focus, to identify, and to recognize the real, the essence; a situation of being pushed to the margin of the field of vision, where identification is possible, but always already particularized – the general is a necessary fiction and cannot be identified. The test image footage taken from television and placed on the lower edge of the picture points to this and simultaneously introduce the element of the modular and mechanical norm to the pictures. Here, the empty middle stands in a constantly redefined, reciprocal, and yet always hierarchical relationship to the identifiable edge, while the basic grid stands for their common constitution. It is the general emptiness that allots the particular its place, but at the same time emptiness is also an absence and even a lack of the particular. Also familiar is the concept of the “empty middle” from political and social theories: the empty center of power permits and forces the particular to make itself identifiable, to take on an identity, to direct itself to become specific in relation to the generality. At the moment when the authority itself becomes identifiable, however, it becomes assailable and is often pushed all to rapidly too the margin. In this sense, the empty middle in the Not pictures is a pulsating and yet hermetic center that exemplifies the virulent problem of the necessity of emptiness as loss and gain.

Anselm Franke